Does there seem to be constant drama in your team?

Often what we don’t realise is that in order to stop the drama, we need to create a psychologically safe environment within the team.

Only once we understand how drama is created and sustained in our relationships, will we be able to take steps to break out of it, and ultimately see the need for increased psychological safety in your team.

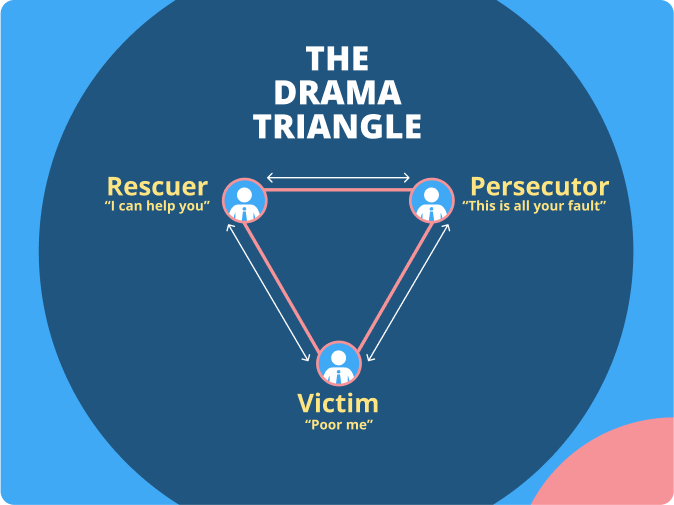

A helpful framework for understanding this drama is called the Drama Triangle.

The Drama Triangle – unhealthy relationship dynamics explained

The Drama Triangle is a very simple, yet insightful model.

Since Stephen Karpman (Karpman’s Drama Triangle) first came up with it in the 1960’s, psychologists have found it very helpful for unpacking what’s going on in unhealthy relationship dynamics.

While studying the way people interact, Karpman realised that each of us has a “script” for the story that we live out in our lives.

He called these stories, “life narratives.”

And he said that if we can explore and understand these narratives, and their scripts, they will help us understand the dynamics that play out in long-term relationships, as well as interactions in the moment.

Karpman’s Drama Triangle explains that we behave in ways that enable our scripts; that we act out these scripts in relation to the scripts of other characters in our story – playing off the scripts they have.

What is important to realise is that drama is created when the characters in the story take on the different roles in relation to each other, but that the drama is sustained when the roles shift from one character to another.

The Drama Triangle in a nutshell:

The Drama Triangle seeks to explain how our behaviours work together to create and sustain relational dynamics.

Karpman suggests that at the heart of any unhealthy life-script, there are three main roles:

- The Persecutor

- The Victim

- The Rescuer

Understanding these will help us understand the dynamics involved in relational drama.

What is important to realise is that drama is created when the characters in the story take on the different roles in relation to each other, but that the drama is sustained when the roles shift from one character to another.

Each character can, and does, play different roles in the same story, in relation to different characters, and at different times and in different ways. Before we dig into each of the three roles it’s helpful to get an overview of the way the roles interact with each other.

How the three roles of the Drama Triangle Interact

In life we can all play each of these roles – Persecutor, Victim, Rescuer – and often more than one at a time.

The different characters overlap, seeing each other in different ways.

Each character has a subjective experience of a story. As soon as anyone person adopts a role, they essentially invite others into the triangle to play the other roles. It’s like throwing a ball to someone, even if they weren’t expecting it, their reflexes kick in and they try to catch it. Most of the time.

We can learn to override those reflexes – we don’t HAVE to fall into these roles, but so often we do. It seems to come very naturally to us. And when we do take on a role in response, we enter the Drama Triangle playing out the script for that role, in answer to the script of the other.

Victims develop and tell themselves “deficiency stories” when feeling small, weak or inferior. With a script that has statements like “I am not enough.” “Life is unfair.” “I don’t know how to” “it’s not my fault”

Victim, Persecutor, Rescuer – which role are you playing?

People with a victim mentality consider themselves weak and abused. They have developed an expectation that they will be taken advantage of – either by circumstances or other people’s actions.

Victims feel sorry for themselves and they expect others to feel sorry for them too. This creates an almost insatiable need for help, and to get it, they tell stories of how hard life is.

They believe, deep down, that because they don’t have what it takes to fix their own problems, someone else must. That others “owe it to them” because, after all, none of this is their fault.

To get the help they want they can become manipulative.

But the kind of help that they need is not the kind of help they want. Someone with a victim mentality is like the beggar who wants a hand-out, not an opportunity to work. So, typically, they don’t respond well to someone trying to empower them – it goes against the core of their victim identity.

Victims develop and tell themselves “deficiency stories” when feeling small, weak or inferior. With a script that has statements like “I am not enough.” “Life is unfair.” “I don’t know how to” “it’s not my fault” etc.

If Victims remain in the victim mindset, how is it we create drama when switching roles on the Drama Triangle?

Good question.

Victims resonate strongly with other Victims.

If someone near them needs rescuing, then the Victim may take on the role of Rescuer to that person – they identify with the story the other person is telling; they see themselves in it and, just like that, they can switch into Rescuer mode.

Or, they might lash out at that Victim’s Persecutor, rescuing that Victim by persecuting that Persecutor (remember, we can play more than one role at a time).

Also, when a potential Rescuer fails to rescue them, a Victim can turn into a Persecutor, lashing out at the potential Rescuer – regardless of whether that person even chose to be a Rescuer or not.

Often extreme Rescuers are just as messed up as the people they are trying to fix – maybe even more so. But they may not be aware of it themselves. Rescuers may carry beliefs about themselves like: “I know what’s best”… or, “I can fix you”.

Rescuers want to help.

The help they offer could be physical, emotional or psychological. But their help, by nature of the dynamics in the Drama Triangle, isn’t actually always helpful. Just like the Victim, they have an identity that is strongly connected with the script for this role.

They like being the one who solves, fixes or helps – there is an emotional and psychological reward for them when they step in. So they might actively seek out people who they can help – always looking for someone to rescue.

By offering advice and support, Rescuers are able to feel needed, useful and important. It gives them purpose. They are proud of being in the “fixer” role. And they might crave the praise they get as a result.

They know how to build the right relationship “the right way”, how to cure every illness “the right way.” They know how to provide psychological support in “the right way,” how to rescue Victims in “the right way.”

Basically, they know everything.

Often extreme Rescuers are just as messed up as the people they are trying to fix – maybe even more so. But they may not be aware of it themselves. Rescuers may carry beliefs about themselves like: “I know what’s best”… or, “I can fix you”.

Rescuers think that the Victims they help will ultimately be able to take responsibility for their own lives. But they fail to see that their continuous intervention actually enables the Victim mindset and disempowers them even more.

They don’t see that Victims might have everything they need to solve their own problems. And fail to see that by their constant rescuing they prevent Victims from developing their own potential – keeping them in a Victim role and script.

The Persecutor stands for truth, fairness and justice. At least, from their own perspectives. This role sees itself as the “upholder” of ideals, values and convictions (the ones they are committed to) and they can be fanatical in their attempts to uphold them.

This approach can be incredibly judgelike (judgemental?) and self-righteous. It makes people inflexible and therefore unable to view situations from a different perspective. And, of course, it turns people into Victims when they are not able to uphold the Persecutor’s ideals.

Fanatics and activists can fall into this role very easily, as can religious fundamentalists.

Persecutors have no shortage of “negative feelings and emotions towards people or situations”. They feel resentment, aggression and irritation which is then aimed at the one who is unlucky enough to have fallen short of their ideals.

Persecutors do not like being perceived as weak, or wrong. So they deny their own feelings and vulnerability, hiding any hint of imperfection, hypocrisy, mistake or helplessness.

On the surface there is an attempt to change the behaviour of those who fall short, but underneath, Persecutors are trying to create a self-righteous place of safety for themselves.

This might be based on their fear of becoming a Victim themselves. So they feel they need to protect themselves through defending these ideals. And they do this by trying to control the world and people around them.

This creates a certain level of apparent certainty and stability for them, but judgement for others. Instead of problem solving or taking responsibility for themselves, they focus their attention on persecuting others – preferring to blame and push responsibility onto others instead of addressing their own insecurities.

But while the Persecutor may feel they are building a place of safety for themselves, this position is a very precarious one.

Persecutors are in danger of falling off their high horse, becoming Victims to their own inability to live up to their ideals – Victims of their own judgement.

Get out of the Drama Triangle and Increase Psychological Safety

Unless your team begins to function within a psychologically safe environment, you will continue to play out the roles with the Drama Triangle and the associated behaviours.

There is an answer to the Drama Triangle and the roles we get sucked into.

By harnessing the power of The Empowerment Dynamic, you and your team can move away from acting out the Drama Triangle and journey towards increasing your psychological safety, and ultimately your effectiveness as a team.

You can get access to Beyond Psychological Safety, a resource we put together to give you insight into what psychologically safe teams look like, what it looks like when teams are not safe, and how to move towards a more psychologically safe work environment.