Victim, Persecutor or Rescuer – Which Role Do You Play in the Drama Triangle?

Is your life a constant drama?

Maybe it’s someone else you know? Somehow they always seem to attract drama. It’s like a never-ending Netflix series!

Ever wished you could make the drama stop?

Find a way to end the constant emotionally charged battle that repeats itself in your life?

Only once we understand how drama is created and sustained in our relationships, will we be able to take steps to break out of it.

A helpful framework for understanding this drama is called the Drama Triangle.

The Drama Triangle – Unhealthy Relationship Dynamics Explained

The Drama Triangle is a very simple, yet insightful model.

Since Stephen Karpman¹ (Karpman’s Drama Triangle) first came up with it in the 1960’s, psychologists have found it very helpful for unpacking what’s going on in unhealthy relationship dynamics.

While studying the way people interact, Karpman realised that each of us has a “script” for the story that we live out in our lives.

He called these stories, “life narratives.”

And he said that if we can explore and understand these narratives, and their scripts, they will help us understand the dynamics that play out in long-term relationships, as well as interactions in the moment.

Karpman’s Drama Triangle explains that we behave in ways that enable our scripts; that we act out these scripts in relation to the scripts of other characters in our story – playing off the scripts they have.

It’s a bit like a dance, one dancer’s moves are related to the moves of theother dancer.

The Drama Triangle in a nutshell:

The Drama Triangle seeks to explain how our behaviours work together to create and sustain relational dynamics.

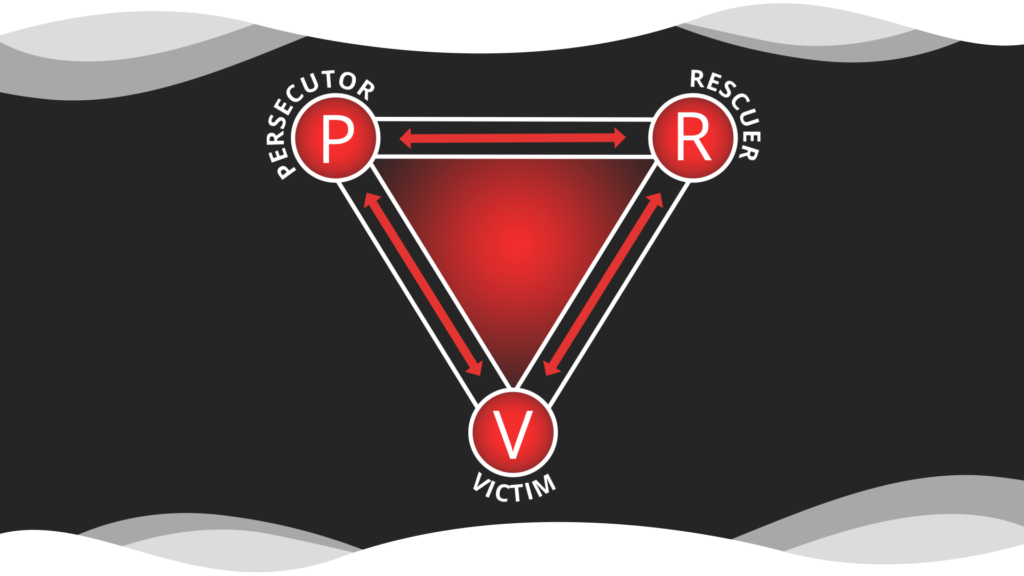

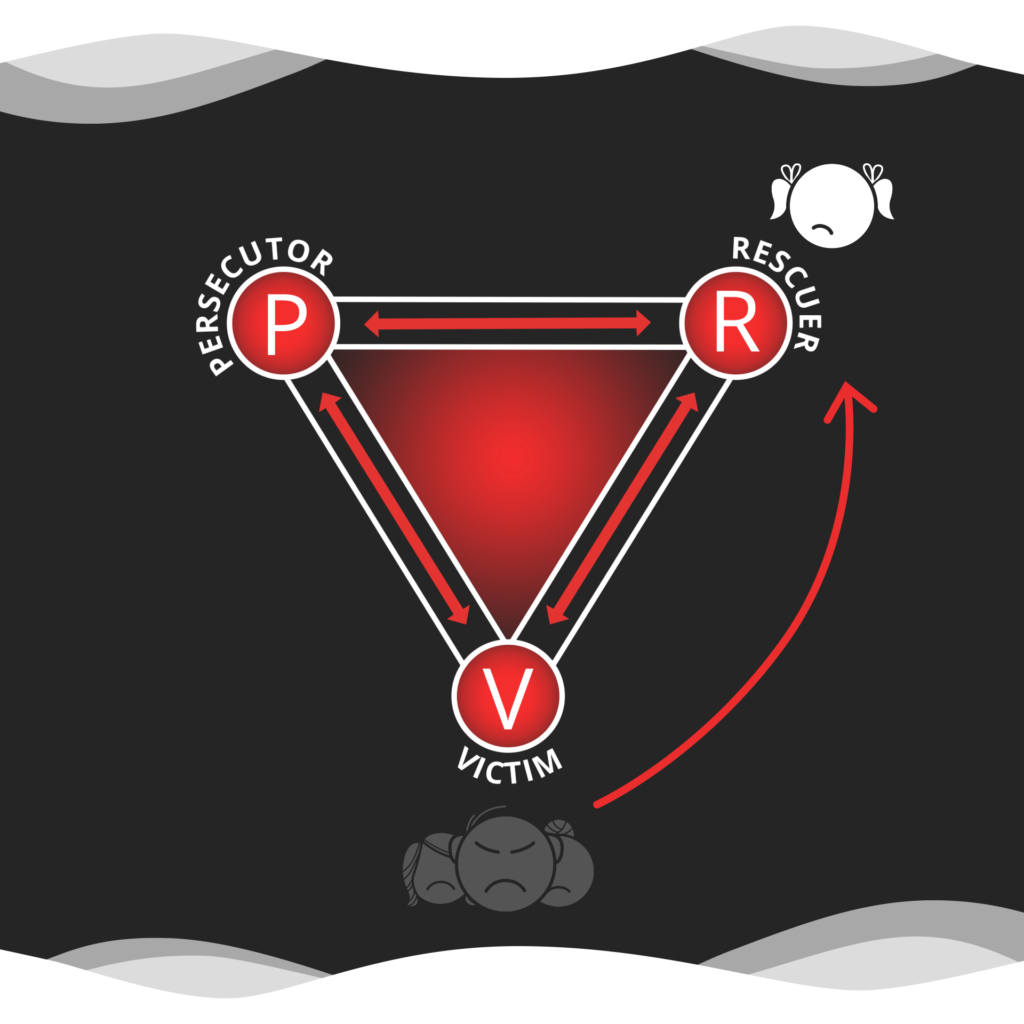

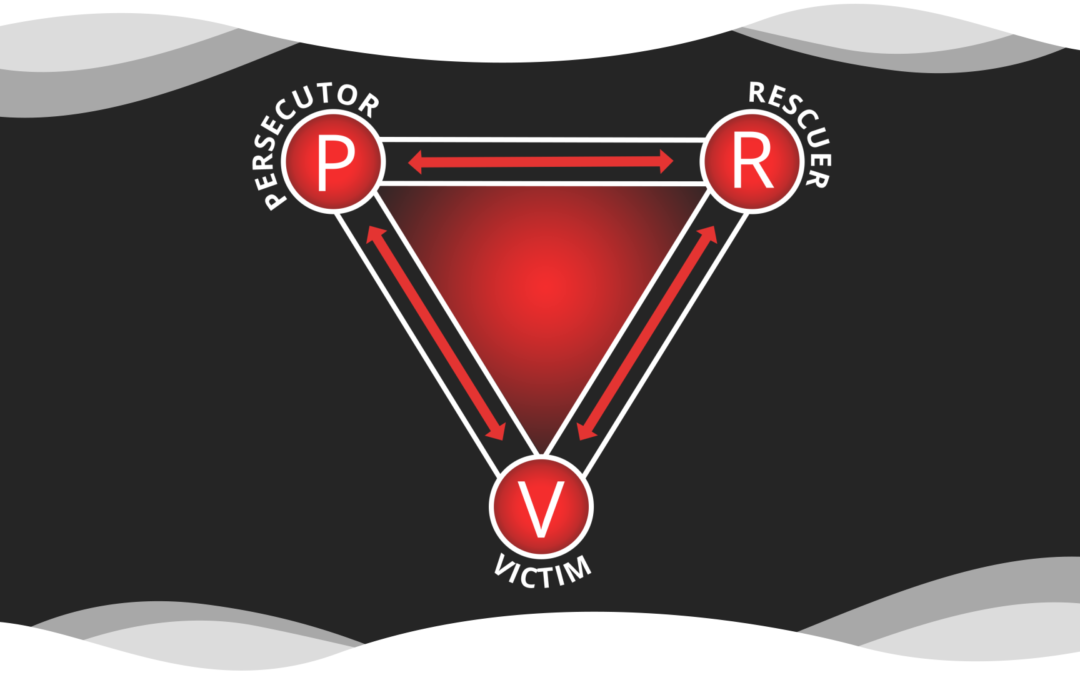

Karpman² shows that at the heart of any unhealthy life-script, there are three main roles:

- The Persecutor

- The Victim

- The Rescuer

Understanding these will help us understand the dynamics involved in relational drama.

What is important to realise is that drama is created when the characters in the story take on the different roles in relation to each other, but that the drama is sustained when the roles shift from one character to another.

Each character can, and does, play different roles in the same story, in relation to different characters, and at different times and in different ways.

Before we dig into each of the three roles it’s helpful to get an overview of the way the roles interact with each other.

How The Three Roles of the Drama Triangle Interact, using Little Red Riding Hood to Illustrate

The Drama Triangle is NOT a Fairytale

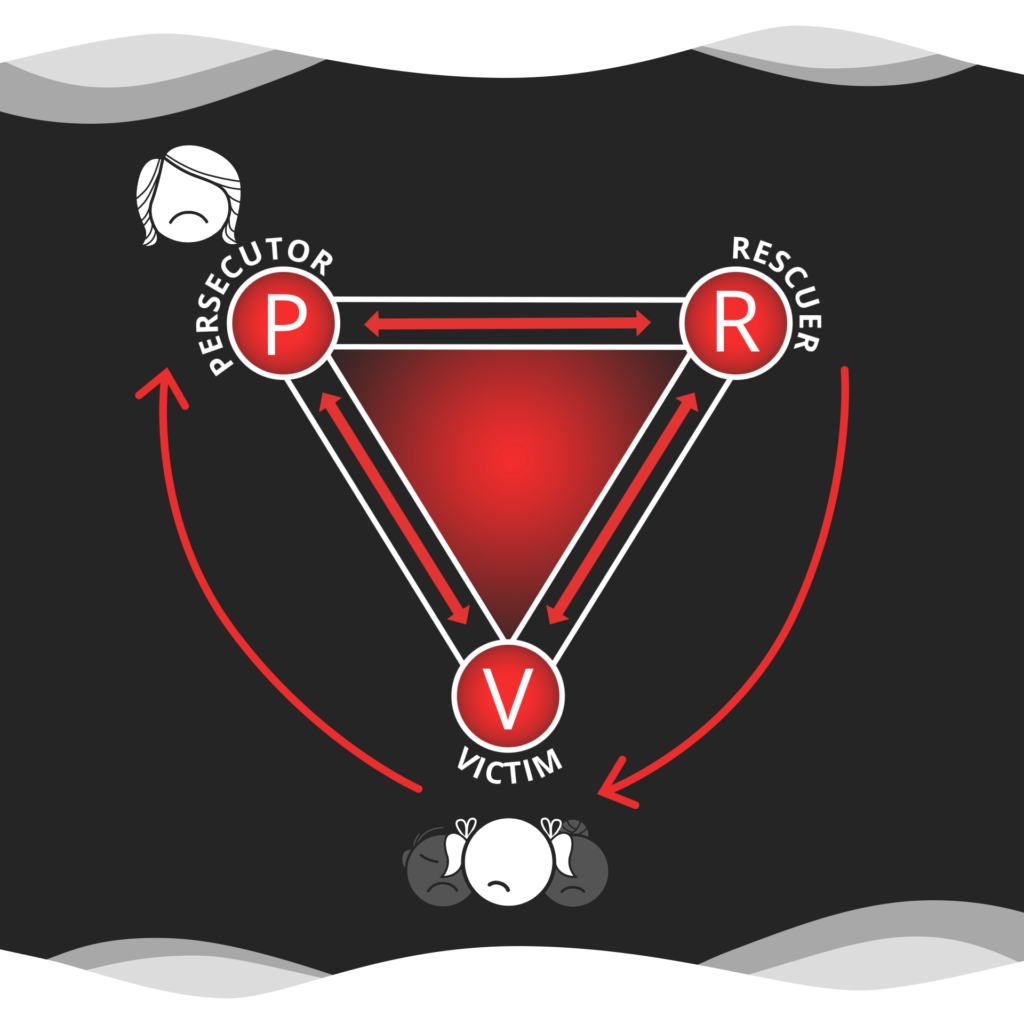

In life we can all play each of these roles – Persecutor, Victim, Rescuer – and often more than one at a time.

The different characters overlap, seeing each other in different ways.

Each character has a subjective experience of a story (Red Riding Hood sees the wolf as her Persecutor, the wolf sees the woodsman as his Persecutor).

But life is a lot more nuanced and complicated than fairy tales.

Our persecutors don’t always have large teeth or an axe – in real life, these roles are much more subtle.

As soon as any one person adopts a role, they essentially invite others into the triangle to play the other roles.

It’s like throwing a ball to someone, even if they weren’t expecting it, their reflexes kick in and they try to catch it. Most of the time.

We can learn to override those reflexes – we don’t HAVE to fall into these roles, but so often we do. It seems to come very naturally to us.

And when we do take on a role in response, we enter the Drama Triangle playing out the script for that role, in answer to the script of the other.

Which goes a long way to explain codependent relationships

One way of describing codependent relationships is with the Drama Triangle.

Essentially these are relationships where people are locked into Victim/Persecutor or Victim/Rescuer roles, in relation to each other.

The Victim, in order to maintain their victim script, needs someone else to play the Rescuer, or even the Persecutor – validating their victim script. And vice versa.³

Understanding the dance between the different roles, and choosing to respond from a new script (not from the Drama Triangle) will help us interact with appropriate healthy behaviour, turning the drama into appropriate healthy interaction.

Real Life Drama Triangle: The Johnsons

Meet the Johnsons. They’re a fictitious family.

The Johnson home is very dramatic.

Mrs Johnson is a victim of hard circumstances in life. She was orphaned at a young age, and had children very young too. The context of her story means the children were victims of that story as well – victims of a mother who wasn’t coping with life.

In time she and her children were rescued by an older man, Mr Johnson, only to realise in time that he was actually a new persecutor – not just for her, but a persecutor to her children too.

Mrs Johnson was an A-type personality – very strong, very extroverted; street smart. She was toughened by a hard life.

Her eldest child, Angela, was also a very strong personality, and as a teenager was very defiant.

And, of course, Mr Johnson was very controlling too, and the alcohol made it worse.

He made sure none of them ever forgot that this was his home, that he had so generously opened up to them – “rescuing” them from what life would have been without him.

The youngest child, another girl, Susie, was at the bottom of this hierarchy of strong personalities. She learnt to be a peace-maker very early on, with a well-developed people-pleasing streak.

You can imagine how the Drama Triangle played out at the dinner table.

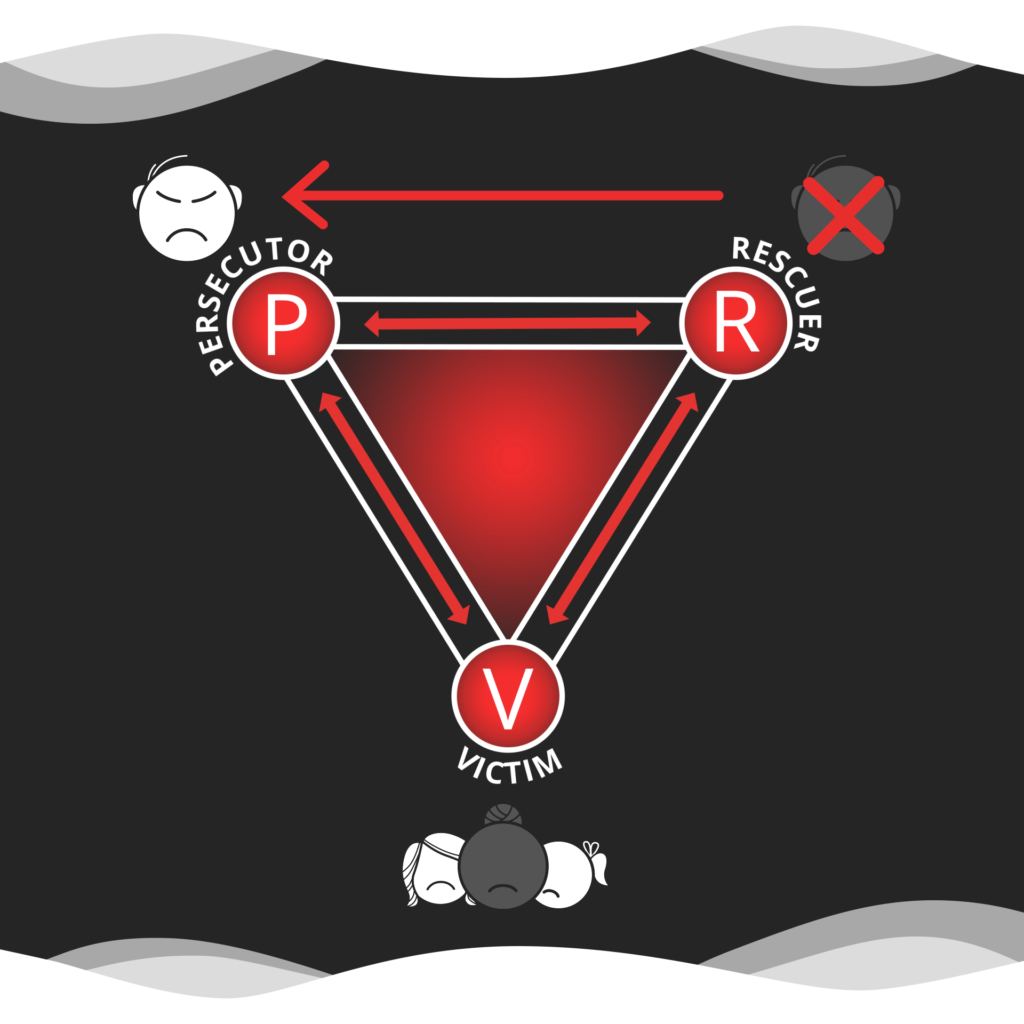

Mr Johnson believed he was the family’s Rescuer, but they experienced him as the Persecutor. He would make a comment at the dinner table, aimed at one of the children – his Victims.

Mrs Johnson would jump to their defense as Rescuer. Sometimes this response was aggressively verbal, sometimes it came out passive-aggressively, just through body language.

This turned Mr Johnson into the Victim of Mrs Johnson’s maternal protection.

In an effort to bring peace, Susie would try to lighten the situation, inadvertently acting as the new family Rescuer. Perhaps not specifically for her step-dad, but to bring peace in the moment.

She would do this by changing the subject, or making a joke.

And sometimes this would set Angela off, who didn’t appreciate that Susie was making light of the situation – defending Mrs Johnson, as if Susie was persecuting her, the new Victim.

Now, Susie was OK with being the Victim, because as long as she was the Victim, no-one else was. So even then she sacrificially felt like she was a Rescuer, just by diverting attention.

This drama triangle played out over and over again in the Johnson home.

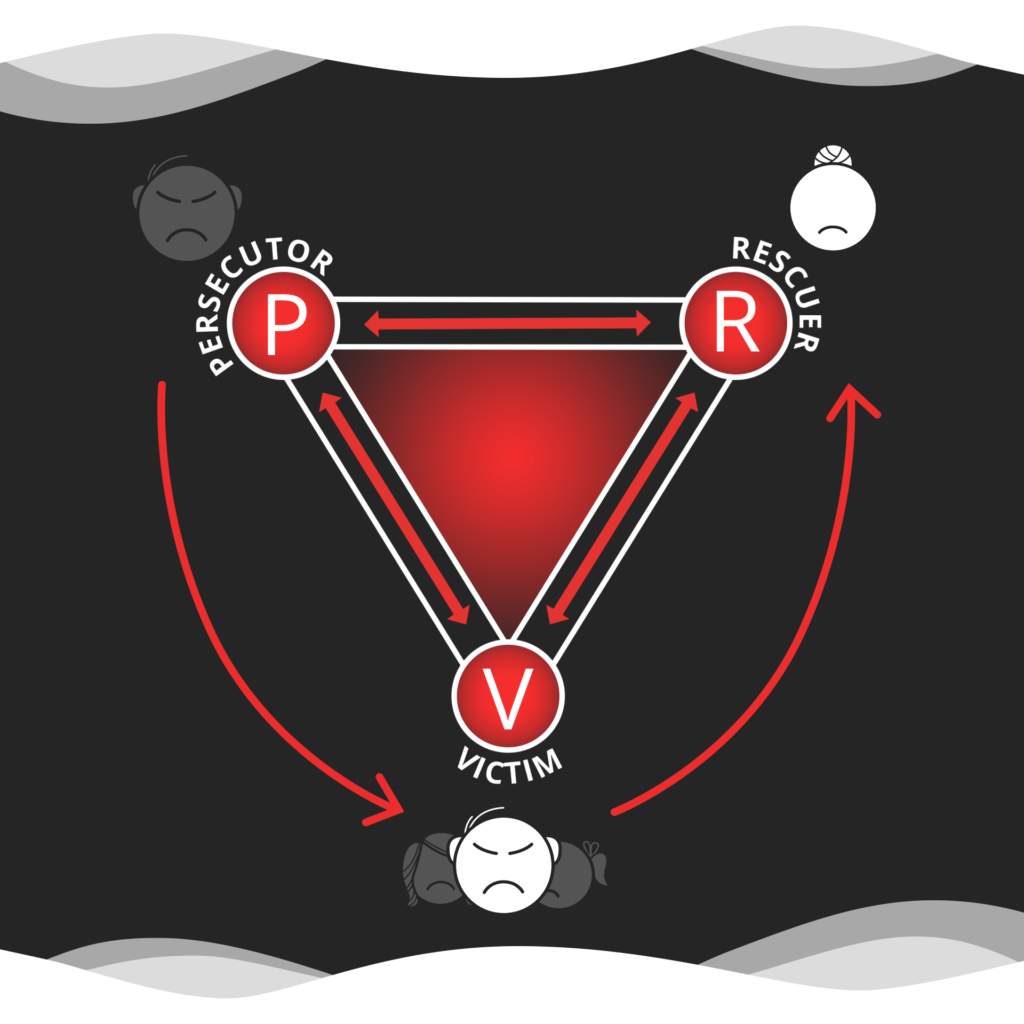

Sometimes Mr Johnson wasn’t even involved. Sometimes it was when Mrs Johnson and Angela butted heads, with either of them as the Victim or the Persecutor of one other, and Suzie the Rescuer.

Suzie would find herself playing into the triangle in whatever role was necessary.

And then, of course, as Susie got older and more independent, her responses would be more rebellious, turning her into a Persecutor too.

Each Character Plays all the Roles

Each of the Johnsons played each of the roles in different ways, often in the same event.

When you come to the defense of a Victim, as the Rescuer, so often you simultaneously become the Persecutor of that Victim’s Persecutor – the woodsman rescues Red Riding Hood by persecuting the Wolf, the Victim’s Persecutor.

So, it’s important to remember each character can play different roles at the same time.

[Around now you may be feeling despondent – it sounds like it’s all bad news and that we’re doomed to repeat these unhealthy cycles of behaviour.]

But it IS possible to get out of Drama Triangle behaviour.

Before we explore how to get out of Drama Triangle behaviour (we do so in our Empowerment Dynamic blog) it’s essential to take a closer look at the three roles, to understand their motivations and scripts.

We’ll begin with a picture of these three roles – Victim, Persecutor, Rescuer – in the extreme, in order to understand the possibilities of how these roles might operate, in a worst case scenario.

Things aren’t this extreme for most of us. Nevertheless, the contrast of the extremes can help us understand the dynamics better.

Victim, Persecutor, Rescuer – Which Role Are You?

People with a victim mentality consider themselves weak and abused.

They have developed an expectation that they will be taken advantage of – either by circumstances or other people’s actions.

They have an “external locus of control” – life happens “TO” them.

So they don’t take responsibility for life’s misfortunes – it is always something, or someone, else’s fault. They have relinquished responsibility.⁴

Victims feel sorry for themselves and they expect others to feel sorry for them too.

This creates an almost insatiable need for help, and to get it, they tell stories of how hard life is.

When people take the bait – accepting the implicit invitation to rescue them – then their Victim role is validated. This becomes, not just a mindset, but an identity, a “life narrative” or a “script” that they live by.

They believe, deep down, that because they don’t have what it takes to fix their own problems, someone else must. That others “owe it to them” because, after all, none of this is their fault.

To get the help they want they can become manipulative.

But the kind of help that they need is not the kind of help they want. Someone with a victim mentality is like the beggar who wants a hand-out, not an opportunity to work.

So, typically, they don’t respond well to someone trying to empower them – it goes against the core of their victim identity.

They choose, instead, to believe the messages that confirm their existing story and identity.

It’s not easy to help victims to take responsibility for themselves. They want you to fix the situation.

But this inadvertently keeps them locked into the victim identity, because when they won’t help themselves, and when your attempt to fix the problem for them isn’t successful, they feel they can now legitimately blame their new failed situation on you.

When you add all of these things together it creates maladaptive self-talk, which continues a downward spiral of disempowerment.

Victims develop and tell themselves “deficiency stories” when feeling small, weak or inferior.⁵ With a script that has statements like “I am not enough.” “Life is unfair.” “I don’t know how to” “it’s not my fault” etc.⁶

If Victims remain in the victim mindset, how is it we create drama when switching roles on the Drama Triangle?

Good question.

Victims resonate strongly with other Victims.

If someone near them needs rescuing, then the Victim may take on the role of Rescuer to that person – they identify with the story the other person is telling; they see themselves in it and, just like that, they can switch into Rescuer mode.

Or, they might lash out at that Victim’s Persecutor, rescuing that Victim by persecuting that Persecutor (remember, we can play more than one role at a time).

Also, when a potential Rescuer fails to rescue them, a Victim can turn into a Persecutor, lashing out at the potential Rescuer – regardless of whether that person even chose to be a Rescuer or not.

[Do you see that these roles are not mutually exclusive?]

Rescuers want to help.

The help they offer could be physical, emotional or psychological. But their help, by nature of the dynamics in the Drama Triangle, isn’t actually always helpful.

Just like the Victim, they have an identity that is strongly connected with the script for this role.

They like being the one who solves, fixes or helps – there is an emotional and psychological reward for them when they step in.

So they might actively seek out people who they can help – always looking for someone to rescue.⁷

By offering advice and support, Rescuers are able to feel needed, useful and important. It gives them purpose.⁸

They are proud of being in the “fixer” role. And they might crave the praise they get as a result.⁹

So it’s easy for Rescuers to think of themselves as experts in practically every area of life – they always know the answers, and aren’t shy to share them.

They know how to build the right relationship “the right way”, how to cure every illness “the right way.” They know how to provide psychological support in “the right way,” how to rescue Victims in “the right way.”¹⁰

Basically, they know everything.

And we are soooo lucky to have them (not).

But this doesn’t mean their own lives actually exhibit this “right way,” they just know what it is … apparently.

Often extreme Rescuers are just as messed up as the people they are trying to fix – maybe even more so. But they may not be aware of it themselves.

Rescuers may carry beliefs about themselves like: “I know what’s best”… or, “I can fix you”.

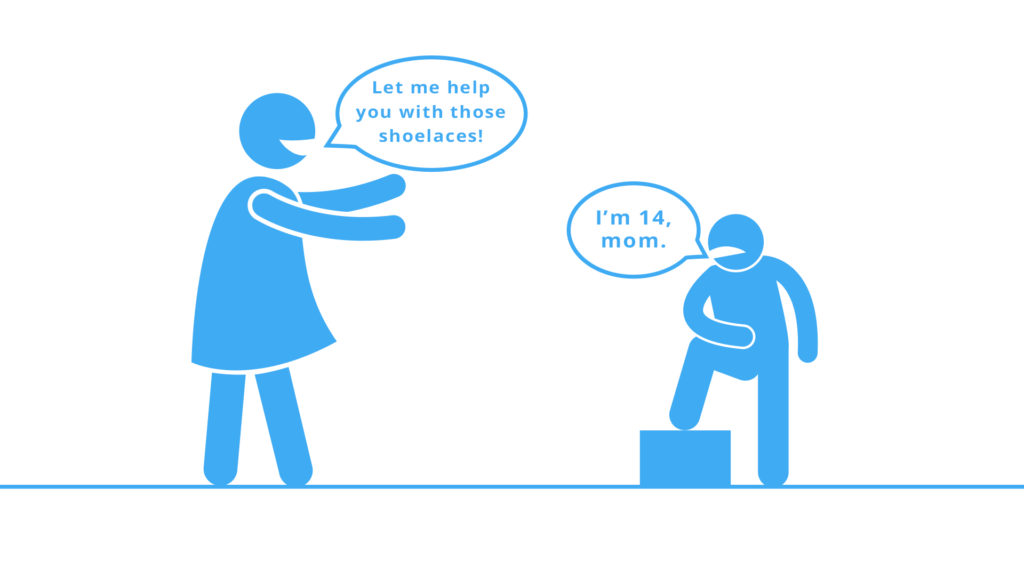

Rescuers think that the Victims they help will ultimately be able to take responsibility for their own lives.¹¹ But they fail to see that their continuous intervention actually enables the Victim mindset and disempowers them even more.

They don’t see that Victims might have everything they need to solve their own problems.

And fail to see that by their constant rescuing they prevent Victims from developing their own potential – keeping them in a Victim role and script.¹²

You can see how a Rescuer–Victim relationship can easily become codependent. When both of them are receiving emotional and psychological reward from playing their respective roles for the other?

An example of a Rescuer is an overbearing parent who struggles to let her children mature into independent adults. Essentially an overbearing parent disempowers the developing child.

The same could be true of one partner in a romantic relationship, or a colleague who always covers for you.

It’s important to see that this identity of being the Rescuer isn’t just because there is a Victim that needs saving. Rescuers have their own story, they may have a need to be a Rescuer.

So their actions can invite someone to play the role of Victim in response to their need to rescue.

They can be role-addicted too, just like the Victim. And this obsessive need is “rooted in their deeply injured personal autonomy.”¹³ So they need to feel needed.

By helping others, a Rescuer might even deny his or her own needs and neglect themselves.

Their efforts to help others stem from the belief that one day their needs will be met too.¹⁴

But when they aren’t, these Rescuers can easily switch into the Victim or Persecutor roles too.

Not every Rescuer has a “saviour complex” but it’s helpful to paint the picture in the extreme so we get a good sense of the dynamics at play for this role.

The Persecutor stands for truth, fairness and justice.

At least, from their own perspectives.

This role sees itself as the “upholder” of ideals, values and convictions (the ones they are committed to) and they can be fanatical in their attempts to uphold them.

This approach can be incredibly judgelike (judgemental?) and self-righteous.

It makes people inflexible and therefore unable to view situations from a different perspective.

And, of course, it turns people into Victims when they are not able to uphold the Persecutor’s ideals.

Fanatics and activists can fall into this role very easily, as can religious fundamentalists.

Persecutors have no shortage of “negative feelings and emotions towards people or situations”.¹⁵ They feel resentment, aggression and irritation which is then aimed at the one who is unlucky enough to have fallen short of their ideals.

Persecutors do not like being perceived as weak, or wrong. So they deny their own feelings and vulnerability, hiding any hint of imperfection, hypocrisy, mistake or helplessness.

On the surface there is an attempt to change the behaviour of those who fall short, but underneath, Persecutors are trying to create a self-righteous place of safety for themselves.¹⁶

This might be based on their fear of becoming a Victim themselves.

You see, under the surface, Persecutors actually believe they are unsafe.

So they feel they need to protect themselves through defending these ideals. And they do this by trying to control the world and people around them.

This creates a certain level of apparent certainty and stability for them, but judgement for others.¹⁷

Instead of problem solving or taking responsibility for themselves, they focus their attention on persecuting others – preferring to blame and push responsibility onto others instead of addressing their own insecurities.¹⁸

But while the Persecutor may feel they are building a place of safety for themselves, this position is a very precarious one.

Persecutors are in danger of falling off their high horse, becoming Victims to their own inability to live up to their ideals – Victims of their own judgement.

This fall from grace is often used as a narrative mechanism in movies or stories:

- The self-righteous prohibitionist devolves into a drunken stupor

- The anti-corruption official takes the bribe and suffers the self-condemnation

So, yet again, we see how even the extreme versions of one of these roles can easily fall into another role in the story.

Understanding the Drama Triangle Helps You Interact with Others

Now you’ve an overview of the roles in the Drama Triangle.

This model is a great tool for helping us develop an awareness of our interactions with others.¹⁹

Because normal people, even if they’re not Victims, Rescuers or Persecutors, still take on these roles in everyday moments.

All three roles in the Drama Triangle are interconnected. They don’t exist on their own but play off each other.

In acting out any of these three roles, the other two roles are usually present – they are needed to create the context for the third, or to keep it in play.²⁰

Get out of the Drama Triangle (yes, you can!)

If these drama roles are the only strategy to get through life, then it will stunt you from moving forward effectively.

It’s vital to get out of Drama Triangle behaviour.

But how does one do that?

We need to find more creative, adaptive or functional ways to work out how to engage well with the people in our lives, and to deal with life’s challenges effectively. (Emerald & Zajonc, 2019).

There is an answer to the Drama Triangle and the roles we get sucked into.

It’s called The Empowerment Dynamic, and like the Drama Triangle it has three roles, each one serves as an answer to the three roles of the Drama Triangle.

Mygrow is an online personal development platform focused on Emotional Intelligence development, a set of skills that make people great at managing themselves and interacting with others. Resulting in more effective leadership, relationships, stress management, decision making, productivity and individual well-being.

The key to dealing with daily stress, relationships and decisions is Emotional Intelligence. It leads to an increase in happiness, well-being and flourishing in almost every aspect of life.

Understanding the Drama Triangle forms part of our module on building interpersonal skills.

Reference List:

- Karpman, Stephen. “Fairy tales and script drama analysis.” Transactional Analysis Bulletin 7, no. 26 (1966): 39-43.

- See note 1 above.

- Steiner, Claude. “Transactional Analysis : An Elegant Theory and Practice.” International Transactional Analysis Association, (2003):1-6.

- Emerald, David & Zajonc, Donna. “The 3 TED * (*The Empowerment Dynamic) Roles: Their Core Beliefs and Aspirations The Creator’s Choice.” (1960):1-7.

- See note 4 above.

- See note 4 above.

- See note 4 above.

- Shmelev, Ilya. “Beyond the Drama Triangle: the Overcoming Self.” Psychology. Journal of the Higher School of Economics 12, 2 (2015):133-149.

- See note 4 above.

- See note 8 above.

- See note 4 above.

- Burgess, Robin. “A Model for Enhancing Individual and Organisational Learning of ‘ Emotional Intelligence ’: The Drama and Winner ’ s Triangles.” Social Work Education 24, 1(2005):97-112.

- See note 8 above.

- See note 4 above.

- See note 8 above.

- See note 4 above.

- See note 4 above.

- See note 12 above.

- See note 12 above.

- See note 8 above.

This was most helpful and very interesting. I can see myself in every roll and am curious to look into this further.